Chloroquine acts on host target respiratory cells by:

Chloroquine increases the endosomal pH required for the virus- host target cell fusion. Increase in the pH disrupts the normal viral function.

In SARS-coronavirus, which is a sister to COVID-19, chloroquine was found to interfere with the glycosylation of cellular receptors of the virus. This interference eventually resulted in no association between the host target cell and the virus.

Chloroquine acts as an ionophoric agent for Zinc ions and thus increases the in flux of zinc ions into the cytoplasm of host target cells regardless whether the host target cells are infected or not.

All the above-mentionedgas mechanism is on the host cells and COVID-19 can not mutate and cause resistance to these 3 mechanisms. First 2 mechanisms inhibit the virus-target host cell union. Chloroquine results in disablement of ACE2 (Angiotensin converting enzyme 2) terminal glycosylation which leads to the morphological change; ACE-2 is a surface receptor found on target host cell. This results in the disruption in the association between the COVID-19 and target host cell as COVID-19 requires ACE-2 receptor to attach to a cell.

Because the action is on the target host cell, Chloroquine won’t develop resistance therapeutically. If a person uses Chloroquine as a prophylactic agent (500mg once in a week for adults and 8.3 mg per kg once in a week for children) against COVID-19 then, it will act pre-infection and post-infection. If a person does not get exposed to the COVID-19 infection after taking Chloroquine (say for 3 weeks) and then some viruses enters and try to infect target host cells, Chloroquine mechanism “a” and mechanism “b” will prevent the union of virus-target host cell. If some of the viruses enters the target host cell, there Zinc ions are waiting to adhere to the RNA dependent RNA polymerase enzyme of the virus and stops COVID-19 polymerization intracellularly. If COVID-19 mutates inside the cell several times, even then the Zinc ions will actively inhibit the viral multiplication inside the host respiratory cells, irrespective of the viral strain. Even if COVID-19 virus manages to escape from Zinc ions trap and releases from the host target cell cytoplasm into the interstitial matrix, intercellular space, and tried to re-infect some of the healthy target host cells, Chloroquine will prevent the re-union of viral genome with target host cells via mechanism ‘a’ and mechanism ‘b’ and the infection will halt in the preliminary stages itself and complications like COVID-19 pneumonia will not develop. Chloroquine molecules will not lose its effectivity in an individual pre and post infection.

Zinc is present in ample amount in the human body. In normal conditions, the Zinc is not present in free state in the cell. The increased level of Zinc ions is not toxic to the cells and cells excrete the extra Zinc ions into the extracellular space. Zinc is commonly present in red meat, legumes, nuts, milk, cheese, eggs, whole grains etc. Garlic increases the absorption and bioavailability of Zinc inside the body. So, some persons who aren’t taking Zinc rich foods in ample amount should eat zinc supplements or garlic daily.

Safety of Chloroquine is well tested as it is given for

Malaria prophylaxis

Autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis

Lupus erythematosus

Now a days it is indicated into the SARS infection as it is a broad antiviral agent.

Through it ionophoric action for its zinc intracellular influx, chloroquine is also used as anti-cancerous drug.

The long-term use of chloroquine (4 years together) may cause its accumulation in the eye. There are some concerns of its use in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme deficient children but the recommended prophylactic and therapeutic doses, Chloroquine is safe to be used in these children. Some persons may complain of acidity and nausea, but it can be resolved if Chloroquine is taken post meal.

Prophylactic dose in malaria is 500 mg once a week in adults and 8.3 mg per kg once a week in children.

In these doses it will be effective against COVID-19 prophylaxis. The therapeutic doses against COVID-19 as used in China, America and India are Chloroquine 500mg BD for 5 days with other anti-viral drugs like Oseltamivir, Lopinavir, Ritonavir etc. and in complicated COVID-19 pneumonia cases, Chloroquine may be used for 10 or more days in the same amount.

Now comes the actual catch of its technicality to be used prophylactically against COVID-19 action. In India as it is a very cheap, safe and easily available drug and can be prescribed against the Malaria as a prophylactic drug as the summer season approaches. It will surely work prophylactically against the COVID-19 outbreak and we can use this opportunity to prescribe it in larger amount as Malaria is endemic in India. It will act on Malaria and COVID-19 infection prophylactically without it being included in the guidelines.

Trump’s excitement for chloroquine in his announcement can be related with the fact that American researchers are currently working on the Chloroquine drug. Many companies have donated chloroquine to the US for research purpose.

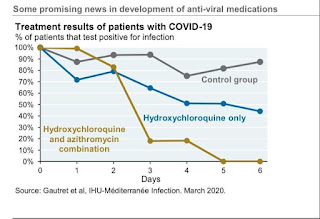

Hydroxychloroquine is less toxic but original Chinese work is based on chloroquine phosphate. Hydroxychloroquine can be used with equal efficacy.

If one starts prophylactically with Chloroquine, then one must stick with chloroquine and must not switch to hydroxychloroquine and vice-versa. This switch may result in increase QT interval.

*REFERENCES*

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020

Gao, J., Tian, Z. and Yang, X., 2020. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. BioScience Trends.

Vincent, M., Bergeron, E., Benjannet, S., Erickson, B., Rollin, P., Ksiazek, T., Seidah, N. and Nichol, S., 2005. Virology Journal, 2(1), p.69.

https://youtu.be/U7F1cnWup9M

SARS-CoV-2 RNA more readily detected in induced sputum than in throat swabs of convalescent COVID-19 patients - The Lancet Infectious Diseases

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(20)30174-2/fulltext